UC Law SF Lecturer Richard Zitrin Shares Trial Lawyering Experiences in New Book

UC Law SF lecturer emeritus Richard Zitrin has written a new book on his decades of experience as a trial lawyer and inherent biases in the legal system.

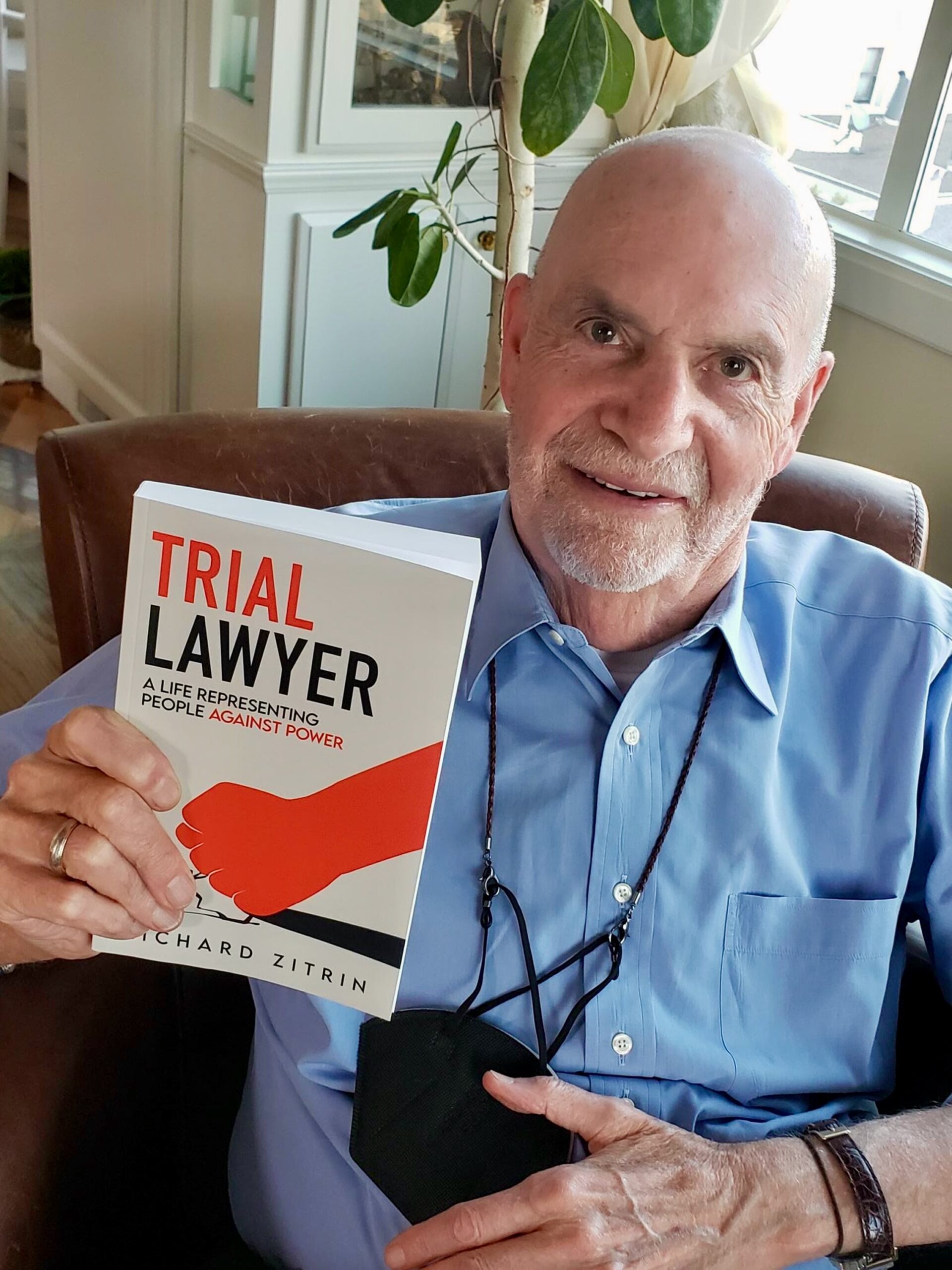

Lecturer Emeritus Richard Zitrin has taught Legal Ethics since 1994 at UC Law SF, and founded USF’s Center for Applied Legal Ethics. For many years the author of a bimonthly column, “The Moral Compass,” for American Law Media, Professor Zitrin’s previous books include Legal Ethics in the Practice of Law (Fifth edition, 2019); and The Moral Compass of the American Lawyer: Truth, Justice, Power, and Greed (2000.) In June 2022, his most recent book, Trial Lawyer: A Life Representing People Against Power, was released.

Throughout your career, you have been an advocate for the poor and disadvantaged, and have actively promoted ethical treatment for all under the law. How does your new book reflect this personal philosophy?

My book is less a pure memoir than a book about the inherent biases of the legal system. Specifically, biases towards people of color, the poor, the less educated, and those who just don’t fit the mold of whatever society considers “normal.” The George Floyd incident was especially illuminating for me. It had the effect of making me take a deep dive into my own white privileged background. I gained a more thoughtful appreciation of the disparity between my clients and the legal system – including lawyers, judges and myself.

Professor Chad Williams, the Chair of the African American Studies at Brandeis University, very kindly wrote about my book that my narrative focuses on “the institutionalized inequities of the legal system, especially as they relate to race and the treatment of Black people, vividly laid bare,” and examines “what it truly means to be an antiracist,” which “by necessity entails personal risk, ethical grounding, and an unswerving commitment to justice.”

How would you say your experiences at Hastings affected the writing of this book?

In my ethics classes at UC Law SF, I have always addressed morality as well as ethics. This includes respect for clients and their autonomy, and the paramount importance of building a client’s trust. In these discussions, it’s impossible not to mention the inherent biases of the legal system, as well as the dangers of Big Law.

As an aside, I’d like to thank my good friend, UC Law SF Professor Richard Boswell, for his kindness and generosity in helping me present my book to others.

Do you have any advice for law students?

In my last few years of teaching, the first thing I told my classes was to be happy in your professional life. Be content. Do what you want, not what your family, friends, and especially your bosses, want. Find your passion. Also, never lose sight of doing what you know is right. We don’t always know what the truth is, but we know a lie when we hear one. We don’t always know what’s fair, but we know what’s unfair. This is a lesson I hope is in the book.

What makes this book different from other law books?

This is a trade book, not an academic work. So, my intended audience is anyone who’s interested in how the law is practiced in real life. While I didn’t write this book for use in law school, it actually may be a pretty good fit. Already, law school classes are using the book for criminal law seminars and trial advocacy classes, because it combines legal ethics and trial advocacy in one volume. These dual interests have been my two careers, so perhaps that makes sense.

Please discuss your bill, SB 1149: “The Public Right to Know Act.”

The idea is, it’s fundamentally unethical for lawyers to keep information secret that could provide information about direct threats to public health and safety. For the past twenty-five years, my passion has been to advocate for what I call “sunshine in litigation.” I believe all information should be revealed in the discovery process, under the public’s right to know. Despite our superb team – and easily passing in the state Senate – the bill failed in the California Assembly in late August. But the driving idea behind it still needs to be addressed. SB 1149 isn’t the first bill I’ve written, and it won’t be the last.

The last chapter of my book focuses on how I became interested in transparency –a case I tried on behalf of a poor Latina against Chrysler Corporation. Because we went to trial, we got the defect information to be public. But the forces aligned against disclosure of information are powerful players in the law: big corporations, chambers of commerce, and other monied interests.